“In the absence of certainty, bullshit blooms.â€

, but the statement could well have served as a seven-word pitch to potential publishers, citing the need for such a volume.

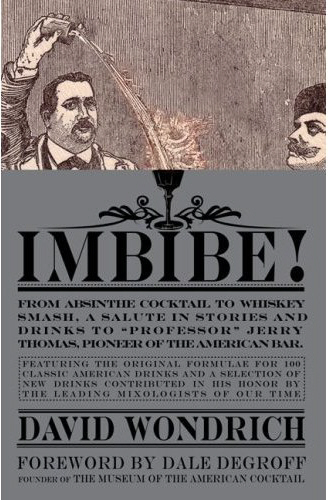

In his magazine pieces and online articles (which now seem to have vanished into the digital wilderness over at Esquire.com), as well as in his previous two books dedicated to the craft of mixology, Wondrich has demonstrated his deftness as a writer and his authority as a researcher while tossing off short histories, anecdotes and observations about spirits, cocktails and the people who love them. Now, with IMBIBE!, the former English professor blows the roof off the joint, ranging unimpeded by tight word counts or the short-sighted demands of editors while exploring the sporting (read: drinking) world of the 19th and early 20th centuries, especially the times of “Professor†Jerry Thomas and his predecessors, contemporaries and successors.

While Thomas – the author of How to Mix Drinks, or the Bon-Vivant’s Companion, first published in 1862 – has long been celebrated as a Founding Father of mixology, the truth of the matter is his legacy is a hard one to warm up to. While groundbreaking in their era, many of the drinks in Thomas’ book lost their novelty many generations ago. But as Wondrich explains in his introduction, spending time with Thomas’ venerable recipes has a way of opening one’s eyes to the world as experienced by our shaker-slinging ancestors:

While Thomas – the author of How to Mix Drinks, or the Bon-Vivant’s Companion, first published in 1862 – has long been celebrated as a Founding Father of mixology, the truth of the matter is his legacy is a hard one to warm up to. While groundbreaking in their era, many of the drinks in Thomas’ book lost their novelty many generations ago. But as Wondrich explains in his introduction, spending time with Thomas’ venerable recipes has a way of opening one’s eyes to the world as experienced by our shaker-slinging ancestors:

…while I often used Jerry Thomas’s book as a sort of historical backstop, a place to trace a particular recipe back to, I rarely mixed any actual drinks from it. At first glance, the book’s telegraphically phrased recipes seemed either uninspiringly simple or dauntingly complex; deeply weird or old hat.

[…]

Time after time, what seemed plain on the page turned out to be subtle; what seemed baroque or fussy, rich and rewarding. But this is only proper. The average nineteenth-century drinker was accustomed to having his drinks—based not on a thin and anodyne tipple like vodka, but rather on something robust and flavorful, like cognac, rye whiskey, Holland gin, or brown sherry—made with fresh-squeezed juices, one of several different kinds of available bitters, hand-chipped ice, and a host of other touches that are today the mark of only the very best bars. In presenting the recipes I’ve done my best to lay bare these touches; to transmit the techniques and competencies the bartender relied on in practicing his craft; in making a few cents worth of whiskey, sugar, and frozen water into a glimpse of a better world.

Wondrich pieces together not only the (scant) known details about Thomas’ life, but reaches back further, into the Colonial punchbowl and the Polk-era tavern, illuminating other masters of the craft such as Willard (whose first, or last, name is lost to history), the “first celebrity bartenderâ€; and William Pitcher, “the Greek-spouting deity of the Tremont House bar in Boston.†He also looks into the future to bartenders of Thomas’s time and beyond, mixologists such as Harry Johnson and “The Only William†Schmidt. And while relatively little is known about Thomas himself, Wondrich fills in the gaps in Thomas’s biography by describing the life of the sporting fraternity—a member of which Thomas was in good standing:

[The sporting fraternity] didn’t look at sports the way you or I might. While it might maintain a general, conversational sort of interest in all species of contests of man against man, man against beast, beast against beast or anything against the clock, when it came right down to it there were only two sports that really counted, and you didn’t actually play either of them. You watched them from a safe distance, limiting your participation to the realm of speculative finance. The Turf and the Ring.

In this milieu, Thomas was a key player, and his career as a bartender was touched by what Wondrich terms the three ages of mixology, ranging from the birth of the republic to the onset of Prohibition: the Archaic (typified by drinks such as punches and flips, fortified with robust wines and spirits, sweetened with sugar cut from loaves and fleshed out with baskets of eggs and buckets of cream); the Baroque (which began around the time of Thomas’s circa 1830 birth, and was typified by iced drinks such as cobblers and cocktails – heavy on the brandy and Holland gin – prepared in shakers and bar glasses and served with the aid of strainers); and the Classic (beginning around 1885, coinciding with a profusion of glassware and bar tools, and marked by the growing use of vermouth and fruit juices in cocktails, which were increasingly mixed with spirits such as whiskey and dry gin).

But while a survey of the drinks of past eras can be enjoyed from an academic angle, this is mixology, an interactive form of art best appreciated by those with open gullets and unquenchable thirsts. After spending the first 48 pages re-creating the mid-19th century world Thomas inhabited, along with the evolutionary path the drinks followed, Wondrich chalks up his cue with a short but immensely valuable survey of spirits and bar tools, then runs the table for the rest of the book, working methodically through chapters on punches; “the children of punch;†egg drinks; toddies, slings & juleps; and, ultimately, cocktails (a couple of chapters on current drinks and bitters & syrups are tacked on for good measure).

It’s in this latter section of the book where Wondrich really cuts loose. Several of the old standard sources are here – Harry Johnson, check; Jacques Straub, check; George Kappeler, check – but relying on old cocktail manuals would be way too easy, and inefficient, for what Wondrich has in mind. From the Steward & Barkeeper’s Manual from 1869, through the Brooklyn Daily Eagle to the Police Gazette to obscure 19th century plays and novels – The Adventures of Harry Franco, anyone? – Wondrich reaches for any and all sources that may offer a whiff of information regarding the time, manner and style in which a particular drink may have been prepared. Through it all, he weaves in stories and anecdotes related to the drinks – such as the use of a Whiskey Skin to blind a bartender in 1855 as part of a dispute between the assailant, Pargene, and the bar owner, “Bill the Butcher†Poole (if you’ve read Asbury’s Gangs of New York — no, the movie doesn’t count (though Daniel Day Lewis rocks as the Butcher) — or Luc Sante’s Low Life

, the name should ring a big, scary bell) – that reveal the world of the barroom in the hard-drinking 1800s.

That world was big and brutal, and a few drinks were certainly needed to give it a little luster. While a bowl of punch or a glass of port might suffice for citizens of the old country,

It’s quick, direct, and vigorous. It’s flashy and a little bit vulgar. It induces an unreflective overconfidence. It’s democratic, forcing the finest liquors to rub elbows with ingredients of far more humble stamp. It’s profligate with natural resources (think of all the electricity generated to make ice that gets used for ten seconds and discarded). In short, it rocks.

But if the Cocktail is American, it’s American in the same way as the hot dog (that is, the Frankfurter), the hamburger (the Hamburger steak), and the ice-cream cone (with its rolled gaufrette). As a nation, we have a knack for taking underperforming elements of other peoples’ cultures, streamlining them, supercharging them, and letting ‘em rip – from nobody to superstar, with a trail of sparks and a hell of a noise along the way. That’s how the Cocktail did it, anyway.

After making the archaic world of punches, cobblers, fizzes and egg drinks a bit more user-friendly for the modern-day reader, Wondrich rolls up his sleeves and addresses the cocktail, using the recipes from Thomas’ landmark book as guides, while elaborating on the themes using drinks from Thomas’ contemporaries and successors. Starting with the plain gin (or brandy, or whiskey, etc.) cocktail and stepping through successive levels (improved cocktail, old fashioned cocktail), then really starting to roam with drinks such as the Morning Glory Cocktail, the Widow’s Kiss, the Daiquiri and the Metropole, Wondrich creates a flavor history of the cocktail’s golden years. In the process, he not only paints a background for each drink but cites the historic recipe and the source, along with updated measurements, notes on ingredients, and suggestions for preparing the drink using contemporary spirits and tools. In this way, Wondrich manages to translate the sometimes maddeningly vague or complicated recipes found in vintage bar manuals, and render them not only useful, but interesting, for modern-day mixologists.

Then, there’s the bullshit factor. As Wondrich notes in one of the book’s appendices (while discussing the origin of the word “cocktail,†a bullshit-laden subject if ever there was one), it’s tempting to try to nail down a place, date and rationale for the naming of the cocktail (not to mention the creation and naming of every drink in the canon), but for the most part we’re talking about stuff that happened in bars. While some of the explanations expounded by well-intentioned aficionados certainly sound reasonable in the misty glow of a Manhattan or two, much of what gets cast about as fact or common knowledge is totally bunk. “It’s funny how we’re willing to kick common sense out the door when it comes to thinking about the past,†Wondrich writes, dismissing the theory that cocktails were named for some archaic practice of garnishing a drink with a rooster’s tail-feather. “How would you react if someone stuck a feather yoinked from a bird’s ass in your drink? Precisely.â€

Fortunately, Wondrich’s bullshit detector is well-calibrated, and when coupled with a post-doc’s capacity to research a topic until it calls you “daddy,” the result is a near bullet-proof volume that explores its topic in more depth and detail than any other book on mixography I can call to mind (one of the closest is another recent book, Jeff Berry’s Sippin’ Safari, which required years of interviews and primary-source research in order to chronicle and understand the mid-century Polynesian phenomenon).

If you’ve skipped over all my blather to see if I actually have a point, I do, and it’s this: buy the damn book. It’s a good read; the recipes are user-friendly; and it’s going to redefine the way cocktail fans and booze geeks talk about what we talk about in much the same way that books such as William Grimes’ Straight Up or on the Rocks, Ted Haigh’s Vintage Spirits and Forgotten Cocktails

, and – of course – Wondrich’s Esquire Drinks

have guided our ongoing conversation. I’d like to tell Mr. Wondrich myself how much I value this new book, but my preternatural shyness dictates that every time I run into him I wind up fumbling with my notebook while making vague pronouncements about the weather. So David, if you’re procrastinating on a deadline and wind up slumming about the boozy blogosphere: Thanks for your hard work. IMBIBE! provides the much-needed certainty to mulch down the blossoming bullshit.

[IMBIBE! will will be available November 6, according to Amazon, though apparently nobody told Powells, which has already been shipping volumes out.]

Damn you for scooping me again!! At least I wasn’t too far along in my post when I happened upon your latest update. Expect a Whiskey Skin on Sunday…

Oh, fer cripes sake.

There is no way I can even come close to writing a review of that quality!

It’s just not fair!

Did I drop my notes on this book at the alembic or something? Did you find them?

Just kidding.

can`t wait to get the damn book.

sound like great read.

It was on the shelves at Borders (guess nobody told them, either) this past weekend, so I picked up a copy on saturday. A really, really fun read.

got the book for xmas, so i thought i’d see which recipes you’ve tried & make one for myself…& gosh darn it, they all call for ingredients i don’t have! i’m out of eggs, have no pineapple & only dream of the day i can get genever gin, so i guess i’ll have to be happy with my (adjusted) boulevardier, instead. and i _am_ happy with it.

–cz

[…] had been covered so well by such stellar writers as Paul Clarke over at the Cocktail Chronicles, “IMBIBE! (no, the other one)” and Jeff Berry over at Beachbum Berry’s Grog Blog, (“AN EDUCATED THIRST: PROFESSOR […]

Good post. You make some great points that most people

do not fully understand.

“I’d like to tell Mr. Wondrich myself how much I value this new book, but my preternatural shyness dictates that every time I run into him I wind up fumbling with my notebook while making vague pronouncements about the weather. So David, if you’re procrastinating on a deadline and wind up slumming about the boozy blogosphere: Thanks for your hard work. IMBIBE! provides the much-needed certainty to mulch down the blossoming bullshit.”

I like how you explained that. Very helpful. Thanks.

[…] a feature on what The Big Lebowski has done for White Russians, replete with quotes from David Wondrich, Ted Haigh and Martin […]

What was the book I just saw in your collection on Evening Magazine that appeared to be a very small hardcover with a powder pink cover and (I think) “Pink” in the title? I did not see it on your Books list.

[…] first professional American cockail bars. When he was doing research for his highly acclaimed book Imbibe! he discovered that the amount of Dutch genever imported to America was six times higher than the […]

[…] stieß bei den Nachforschungen für sein Werk Imbibe! auf Quellen, die belegten, dass Genever im 19. Jahrhundert eine von 4 Grundspirituosen für […]

Just found this cartoon featuring Superstar Bartender (Prof.) Jerry Thomas:

http://www.harkavagrant.com/index.php?id=62